In the heart of Ghana’s capital, Accra, hoardings plastered with artistic impressions of an architectural marvel block prying eyes from seeing what lies on the other side.

Depending on who you ask, the planned multi-million dollar building – known as the National Cathedral of Ghana – is either a symbol of the country’s economic mismanagement or a strategic and bold investment.

In a speech at the turn of the new year, just two weeks after Ghana effectively defaulted on repaying most of its external debt amid a mounting cost-of-living and economic crisis, President Nana Akufo-Addo, scoffing at critics, renewed his commitment to the religious building.

“The National Cathedral is an act of thanksgiving to the Almighty for his blessings, favour, grace and mercies on our nation,” the president said at the construction site where a Bible-reading marathon had been taking place.

God, he said, had spared Ghana from conflict that had afflicted many countries, including some of its West African neighbours, who have been dealing with numerous security challenges.

The president then announced a personal donation of 100,000 cedis ($8,000; £6,700) towards the construction costs. It was envisioned to be a sacred space for all Christians, who make up 70% of the population, and where national religious services could take place.

But Mr Akufo-Addo’s enthusiasm for the project has divided public opinion.

Though most of the costs are supposed to be covered by donations, with the state providing the land and some seed funding, critics have queried the amount of money – some $58m – that the government has so far spent in these economically straitened times.

On top of this, the project has been beset by allegations of misappropriation of funds as well as questions over the awarding of the design tender to celebrated British-Ghanaian architect Sir David Adjaye, a situation that caused friction with some of the top Christian leaders who make up the National Cathedral board of trustees.

The authorities reject these claims and the board has approved a financial audit, as well as agreeing to let parliament investigate the way contracts were awarded.

Ghanaian economist Theo Acheampong believes the government’s priorities are misplaced, considering the country’s current economic situation, including a depreciating currency, dwindling foreign reserves and strained public finances.

“This is a generational crisis. Inflation is in excess of 50%, the country is not able to repay its debt, forcing the government to cut back on expenditure. And also at a time the government is seeking a $3bn loan from the International Monetary Fund, the cathedral is not a priority for the nation,” Mr Acheampong said.

Mr Akufo-Addo first revealed plans for the cathedral after he won the 2016 election and the architect was appointed two years later. But work on what the president has referred to as “his gratitude to God” only began in 2022, two years after his re-election.

However, the sound of heavy machinery carving the earth and animated workers shouting over the din at the construction site is no more after MPs refused in December to approve a further budget allocation of $6.3m from the government.

Contributing to a debate in parliament last month MP Sam George, a prominent critic of the project, quoted the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament to excoriate the government.

“Suppose one of you wants to build a tower. Won’t you first sit down and estimate the cost to see if you have enough money to complete it? For if you lay the foundation and are not able to finish it, everyone who sees it will ridicule you, saying: ‘This person began to build and wasn’t able to finish,” his opposition colleagues suitably amused, cheered when he finished reading the verses.

The project cannot be faulted for its vision.

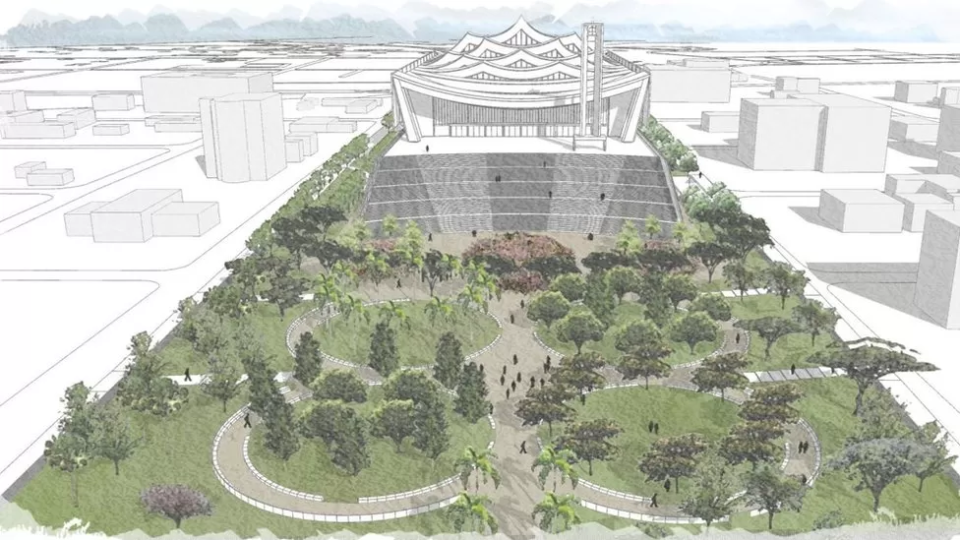

A nine-acre site of prime land between the parliament building, the national theatre and the international conference centre, was hived off for the National Cathedral.

It had earlier been occupied by residential houses for judges, a decision to demolish them sparked its own controversy.

Drawing inspiration from Ghana’s rich arts and culture, the cathedral will have a high pitched staggered roof imitating the architecture of the Akan people. It will also include emblems like the royal stool from the Ashanti people and ceremonial canopies.

Artists from Ghana and other African countries will be invited to create the cathedral’s religious adornment and furnishings.

According to the plan, the main building will have 5,000 permanent seats with room for thousands more, a music school, an art gallery, shops, a national crypt for state burials and it will also be home to Africa’s first Bible museum.

However, the grandeur does not impress its critics.

“Tax-payers’ money should not be used fund a personal pledge to God,” the MP Mr George told the BBC.

He referred to the cathedral as a “vanity project” reminiscent of the The Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro – the largest church in the world – built by Ivory Coast’s independence leader Félix Houphouët-Boigny to transform his hometown.

“We are Christians but the government has no business funding the construction of a religious building,” Mr George said.

Despite the opposition, Paul Opoku-Mensah, the presidential appointee leading the National Cathedral project, remains confident in its viability and sees it as a way to boost the economy.

“Unlike Ivory Coast, we have a strategy of bringing visitors to Ghana. We have to use our religiosity for our own development,” he said.

Mr Mensah has visited the Bible Museum in Washington DC and is negotiating loaning religious artefacts from Israel to display at the cathedral once complete.

The cost of the project has been a moving target, according to critics, who say it has been inflated over time, including a claim that it could rise to $1bn.

But Mr Mensah told the BBC that the building would cost no more than $350m. “That figure is sacrosanct,” he said explaining that the cathedral would be a Christian hub attracting visitors on the continent and beyond making it economically viable.

He also denied claims that the cathedral was the Christian majority’s response to the $10m Ghana National Mosque which was built using funding from the Turkish government. That was launched in 2012.

But Mr Mensah said the project had been “caught up in the divisive politics of our country”, adding that while Ghana’s economic crisis cannot be ignored, critics did not appreciate the viability of the cathedral, which early estimates say could generate $95m in five years.

“We’re looking at what great cathedrals did to Europe by extending the frontiers in music, art and engineering, but given the economic conditions we face, we can review our plan, like do phased construction and reconsider what type of artefacts we install in the building,” he said.

After parliament rejected funding for the cathedral, Mr Mensah said his team was looking at other ways of raising the money.

“We are developing plans for mass mobilisation of funds; like rallying a million Christians to donate $20 a month for two years. We also want to attract donors, the private sector and the diaspora community to contribute.”

Mr Mensah has however not given up on convincing MPs to back funding for the project. He hopes to organise a meeting with them because he believes some do not have a full understanding of the project.

But he too admits the project is under threat and unlikely to be completed next year before President Akufo-Addo leaves office.

“The completion is dependent on our ability to raise the needed resources. That’s what we are focused on now,” Mr Mensah said.